Vacant Quarters

November 1941 | Peru Indiana | 150 wagons burned

The interactive installation, Vacant Quarters, overlays new media technologies with an anachronistic/hand-drawn aesthetic as a participant becomes the onlooker in a cacophonous, escalating event. Though Vacant Quarters reflects a particular moment in history, broad themes of validity, obsolescence, and cultural change are at the heart of this installation and accompanying book.

VACANT QUARTERS INSTALLATION

Programmed in openFrameworks (2011-2012)

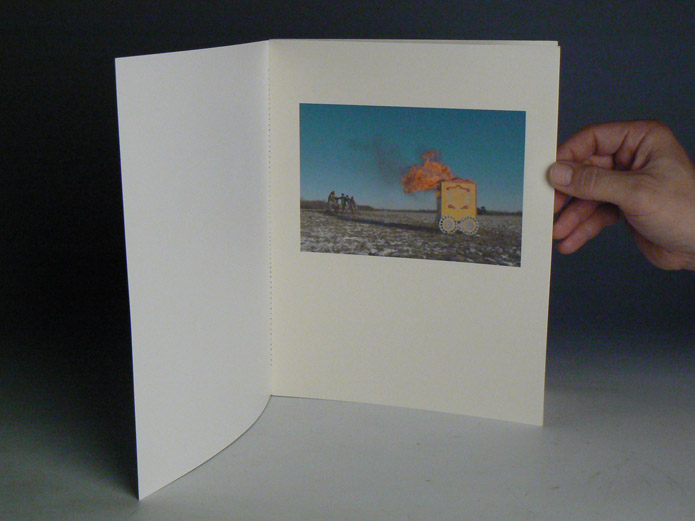

Vacant Quarters uses layering and face capture to bring a participant into a story of change and cultural upheaval. The initial projected image is a magic lantern slide of the 5 Graces circus wagon (built in New York City by the Fielding shop in 1878). If a viewer enters the scene and looks on, a live video of their face appears in a window above the parade. After watching for a few seconds, ghost-like circus wagons begin crossing the screen from right to left, each accompanied by a sound. The sounds and wagons are selected at random by the openFrameworks program.

For each participant, a unique combination of sound and image leads to a unique conflagration; the wagons are set alight as digitized flames fill the screen.

It is the act of looking that causes the wagons to burn, calling into question the passive or active role of a spectator in violence or destruction: What happens if we stand by and watch? What if we simply don’t intervene?

VACANT QUARTERS GALLERY SKETCH

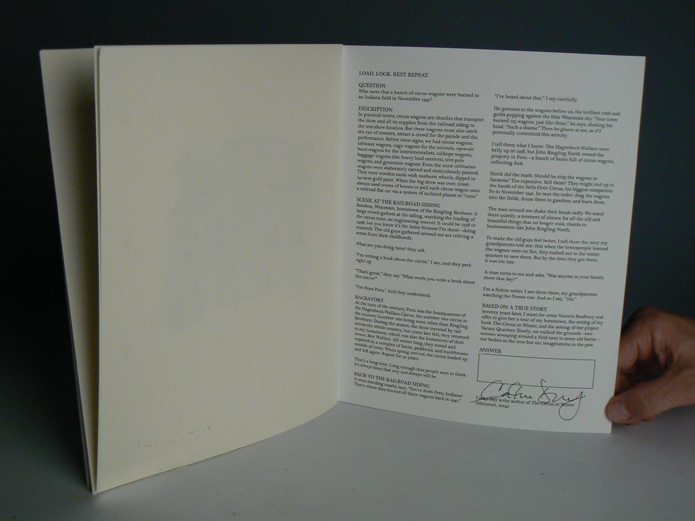

THE SHORT STORY (Historical Background and Contemporary Themes)

To research the historical background of Vacant Quarters, I traveled to Peru Indiana’s Circus Hall of Fame on the property of the old winterquarters of the Haggenbeck-Wallace Circus. Here, I met Tom Dunwoody, a circus historian and miniaturist who dedicates himself on the accuracy of historical reproduction. The metaphor and broader relevance of Vacant Quarters wouldn’t interest Tom, though he was uniquely willing to relay what he knew of the wagon burning incident. While Peru is full of people trying to hold on to their version of Peru’s history, most versions hope to forget this event that happened in November 1941.

In the early 20th century, circuses were networked media in a pre-Internet world. Each circus was a node in a distributed network of regional acts, but by 1941, the world was shifting. The new medium of cinema was beginning to replace and devalue expensive live traveling shows. Only through conglomeration could the circus survive. John Ringling North consolidated regional shows and arranged them into a master franchise. With the circus business in decline, North needed less equipment to run his consolidated business and didn’t want the valuable wagons to get into the hands of another potential mogul.

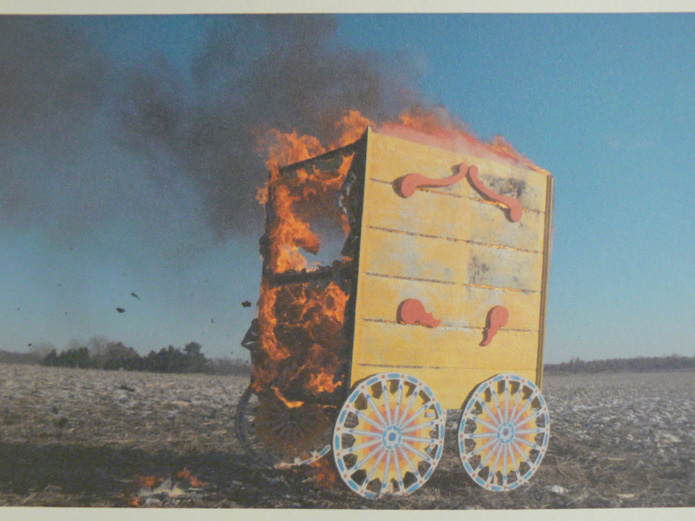

Over the course of three days in 1941, North burned 150 circus wagons on the winterquarters property. As the wagons were burned, the people of Peru came out to salvage their heritage. They rushed to the farm to grab what they could from the growing flames. Peru has seen economic hardship since its primary industry, the circus, was reduced to ashes.

VACANT QUARTERS BOOK

Cathy Day Essay

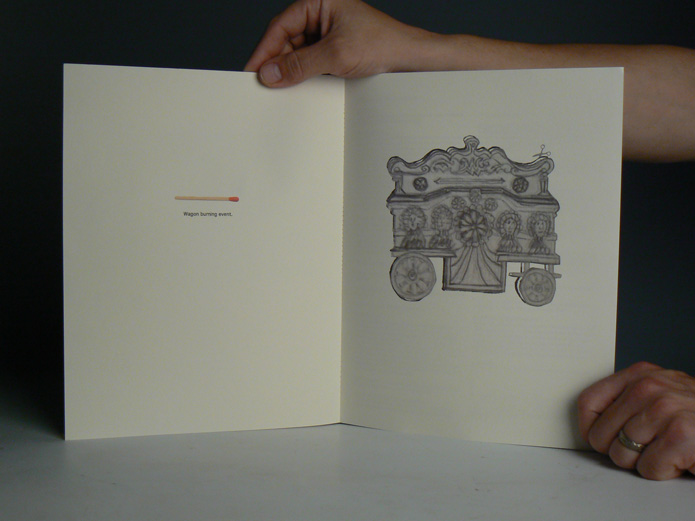

Adjacent to the installation is the Vacant Quarters book, an artist book with prints of a documented re-enactment of the wagon burning event. The book includes an event score for wagon burning, a paper cut-out wagon, an embroidered flame, 2 photographic prints, a magic lantern slide of the 5 Graces, and a short story by Cathy Day, Peru Indiana native and author of the novel The Circus in Winter. This hand-made book is an old-media companion piece to the projected installation.

Vacant Quarters Installation History

Version I (prototype) "Monkey Thunder Boom" 2011 | Muncie IN USA

Version II "Conversation Pieces" 2011 | Purdue IN USA

Version III "Witness Material" 2012 | NY NY USA

Vacant Quarters Research Background (The Long Story):

The broader relevance of the wagon-burning story is that of  sacrifice in the face of technological or cultural change. Obsolescence moves at a much faster pace in today's world when it comes to hardware, software, trends, startups, and computer languages. Useful goods are made and discarded. Technological shifts leave people, homes, and jobs behind.

sacrifice in the face of technological or cultural change. Obsolescence moves at a much faster pace in today's world when it comes to hardware, software, trends, startups, and computer languages. Useful goods are made and discarded. Technological shifts leave people, homes, and jobs behind.

The burning of itinerate objects that were once revered as glorious works of craftsmanship, traveling museums, and parade pieces, suggests a changing world. In Vacant Quarters, participants can only stand by and watch the destruction in which they participate.

The grounds of Peru Indiana’s Circus Hall of Fame served as the winterquarters of the great Hagenbeck-Wallace circus from 1884, when Ben Wallace purchased the track of land by the river. The lowland property suffered a tragic 100-yr flood in 1913 and sustained so much damage that Wallace was forced to sell his circus and his 3,000 acres (including a 200 acre compound with 32 buildings) to Wes Ballard.

Ballard's American Circus Corporation ran five circuses from Peru each season to all corners of the country and nearly had a monopoly on the popular entertainment medium of the day. John Ringling's circus was the only viable competition left and the two sides understood that the war of the great circuses couldn't last. In 1929, Ringling came to Peru to settle the matter. Ringling and two of the men from American Circus Corp entered the Bears Hotel in downtown Peru and sequestered themselves for 3 days. When they emerged, John Ringling had bought out Ballard and the ACC's five circuses for $2 million dollars.

...six weeks later, the stock market crashed and Ringling lost his fortune. All five circuses continued to run out of the winterquarters at Peru, but in 1936, John Ringling died a poor man. John Ringling North, nephew of the first Ringling, took over the estate (even though his uncle had removed him from his will, he stayed on as executor and kept his uncle unburied in cold storage in New Jersey).

As the depression era continued, the circus business declined in step. Each year beginning in 1934, one fewer circus left the winterquarters at the start of the season, until 1938, the last circus, Hagenbeck-Wallace, left Peru. That summer, Hagenbeck-Wallace went broke in California and disbanded.

In 1941, there were still 150 elaborately carved and painted wagons in the barn at the winterquarters. These vehicles "were built like tanks" as Tom Dunwoody said. The wagons were carved by craftsman, many of whom were German woodcarvers who had emigrated to America and continued to practice their trade. Each wagon was a unique design on an individual theme. Artistic license belonged only to the carver who considered each a work of art. Two designs Dunwoody pointed out were the Jardenir, with a floral design, and the Five Graces wagon seen in Vacant Quarters. There were tableaux wagons, cage wagons for animals, band wagons for the instrumentalists, calliope wagons, baggage wagons (the heavy load carriers), pole wagons (for carrying pieces of the tent), and generator wagons (for lights/electrical equipment).

On November 21, 22, and 23, 1941, (oddly, a few weeks before Pearl Harbor), John Ringling had the 150 wagons pulled from the barn, laid out in the winterquarter fields, soaked with gasoline, and burned. People in Peru came out to stop the burning of the wagons. Not only were they part of their history, but they could be used! Few were saved. Why the carts were burned is a complicated matter, but one thing was for sure: what remained of the circus business was going to belong to Ringling. And these wagons, these branches on the tree of cultural dissemination, were a liability to the CEO if they got into the wrong [read: other] hands.